In the Beginning

Before we begin, I’d like to take a few short paragraphs to explain the rationale behind this approach. The more I was exposed to scientific writing, the more I realised that it was really just another form of storytelling. The oldest form of entertainment, and probably the basis of human culture.

A good story has a narrative, a thread if you like, that strings all the events and characters of the story together into a coherent whole. The narrative also provides the perspective of the story. For example, the Three Little Pigs is told from the perspective of three pigs terrified for life and limb (not to mention wanton property destruction). We, the audience, are invited to sympathise with their plight and to dislike the Big Bad Wolf.

However, told from the Wolf’s perspective, it could have been about a single mother Wolf, trying to feed a litter of cubs so they don’t starve. Foiled by her nemesis’ command of the technology of bricks and mortar, she slinks slowly home, her belly growling in anguish. Perspective is hugely important in storytelling.

Stories also have a beginning, a middle and an end. In the beginning we are introduced to the characters and setting. In the middle, the characters we now know usually have to overcome some kind of obstacle to achieve their goals. The ending resolves the story and ties up all the loose threads into a neat satisfying package.

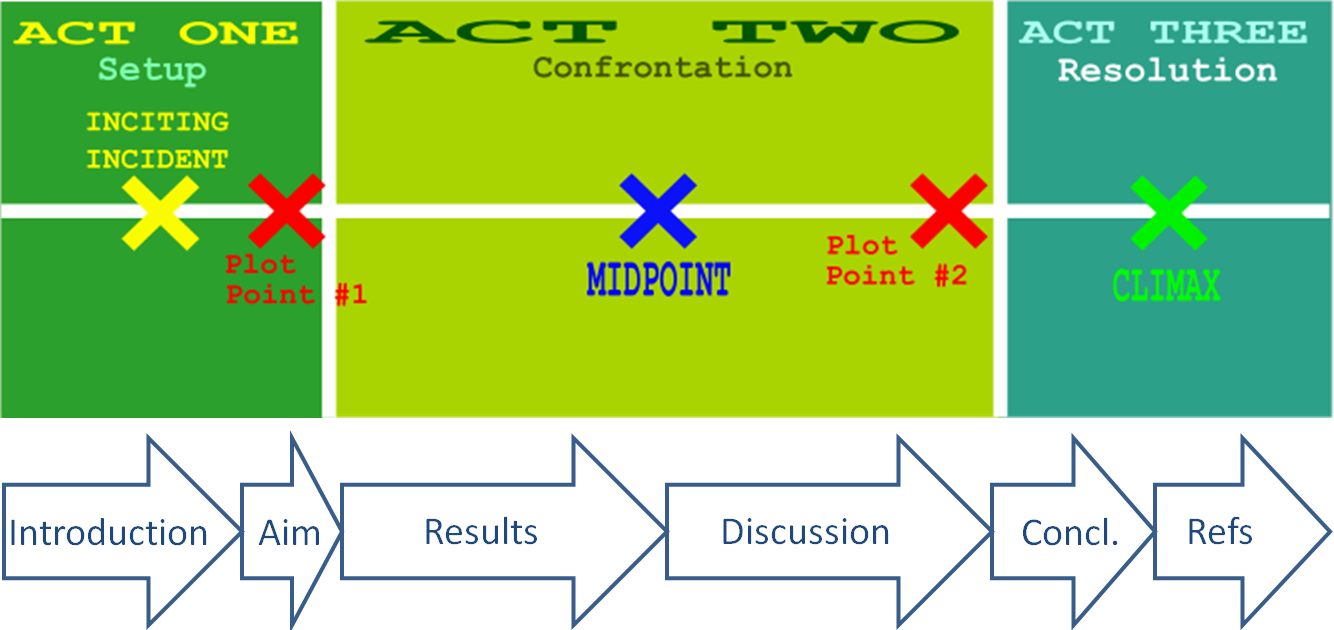

This basic layout is called the three-act structure and it’s used in most Western story-telling, including stage-plays, novels, films, and even songs. It’s familiar to audiences, and because of this, we can use it to our advantage when writing scientific papers - as indeed most papers do.

A question I expect many people to be asking now, is “how exactly does the three-act narrative structure map to a scientific paper?”

An example of how the flow of a scientific paper approximates that of a three-act story. Towards the end of the introduction, the hypothesis is equivalent to the inciting incident. The first plot point is the aim, which gives the story its purpose. The results and discussion make up the second act, with well-founded scientific speculation toward the end of the discussion standing in for the second plot point (although this may not always be present). The conclusion represents the climax, which is then followed by the references section standing in for the end credits. This figure is adapted from work by Bratislav under a Creative Commons Attribution Share Alike 3.0 licence and is presented here under that same licence.

An important thing to note here is that the more you read scientific papers, the more you will see variations of this structure in their presentation. The best piece of advice I can give people learning to write papers is to read them. I cannot stress this enough, even if you don’t understand the scientific jargon, read the papers anyway. The jargon will change from paper to paper, but what remains the same across all of them is the structure of the paper. The way it is presented is the important part. Once you understand that, you can apply it to your own reports and BAM! Quality output ensues :)

Before you put fingers to keys

Before you write anything you need to think about what exactly it is that you’re writing about. For any given paper, the scientists involved have done a heap of work, they’ve conducted a series of experiments, they’ve analysed the results and now they need to report their findings to the rest of the scientific community. Like reporters writing for newspapers (or, if you were born after the 1980s, news/click-bait websites), the first thing they need to do is to decide on a narrative.

Wait. Isn’t that like spin? Isn’t science and the scientific method supposed to be above such foolishness? The answer is that it is and it isn’t. Remember, science is a human activity, so for better or worse, it is still has sticky, gooey traces of humanity clinging to it. The one thing that science has going for it over run-of-the-mill politicking and such, is that scientific papers are also full of verifiable, objective facts and real data. The narrative of a scientific paper is how those facts are communicated. To coin a phrase, what’s your angle?

For example, you’ll often see something along the lines of “this is the first recorded instance of…” or perhaps “here, we show for the first time that…”. The angle here is obvious, the authors want you to know they are the first ones to publish a description of this effect or whatever it is that they’re reporting.

The narrative need not always be so obvious. Scientific papers are often complex beasts with many experiments looking at a variety of things. After performing such a vast array of experiments, the authors analyse the data and perhaps they see a pattern (whether it’s there or not) they wish to communicate to the reader.

Based on what experiments worked and what didn’t, they may present the reader with a story that uses only their best material, or emphasises a particular finding over others. Perhaps when they were doing these experiments they got some results that didn’t fit in with the story they wanted to tell, so they quietly pushed some of those results into the background (or even worse, left them out of the paper entirely - it does happen). This is important, because as a reader of the scientific literature, you have to be able to sort a lot of this out yourself. Sometimes, what a scientific paper is not telling you is almost as important as what it is.

This isn’t to say that narrative is all devious. It’s often used to make a paper more enjoyable. Or to really emphasise how important the authors’ findings are. For example, say that you’ve found the last known breeding grounds for an endangered animal. You could report your findings as doom and gloom, focussing on the destruction of habitat and the possible loss of yet another species. Or you could say this is great. Now that we know where the breeding ground is, we can take steps to protect it and possibly expand it. Since we now know what conditions the creature likes to breed in, we could replicate them elsewhere. It’s all about perspective.