Referencing

Your story has come to an end. You’ve taken the reader on a journey of discovery, you’ve explained to them all about your findings, what they mean and why you think they’re important. Now it’s time to roll the credits.

The Whys of Referencing

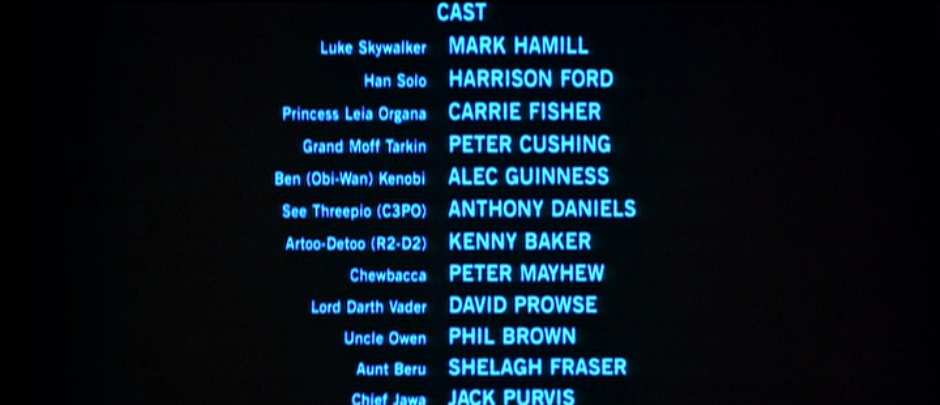

Just like George Lucas would never have been able to complete Star Wars without the help of the hundreds of technicians, engineers, actors, camera operators and other expertise required to get a film onto the big screen; you would not have been able to write your paper without the knowledge you gained from other scientists’ work. It’s important this is recognised, not just so everyone feels warm and fuzzy and appreciated, but because you will have been making claims and interpreting other peoples’ data in your paper and it’s important you tell the reader where you got the information so they can check it for themselves if they want.

Yeah, it's got that guy in it... you know... that one who plays that tough guy in that other one I really like? Oh come on! You know who I'm talking about - he snogged that actress whatsername! Oh forget it, how awesome were the Gaffer, Best Boy and Dolly Grip? Credit: 20th Century Fox/Lucasfilm

Thankfully, there’s a simple rule for referencing: every time you make a claim, you must back it up with the original source material. This serves three purposes. Firstly, it tells the reader you didn’t just make something up out of thin air. Secondly, it tells them who actually found out that piece of information in the first place, giving credit for the work done as well as the source so they can check its veracity for themselves. Finally, it makes sure you aren’t accused of plagiarism, which is very serious in the academic world (so serious, in fact, that instances of plagiarism that occurred thirty years previously have been known to come back to bite people in powerful, very well paid positions; forcing their resignation. Don’t let today’s lazy and easy Wikipedia copying session destroy tomorrow’s salary).

How could you be accused of plagiarism if you aren’t citing references? Put it this way, if you’re making a claim but you aren’t citing a reference, what you’re essentially doing is passing that piece of information off as your own. However, you only know that piece of information because of the hard work of someone else, so it’s important that you acknowledge that.

The Hows of Referencing

Okay so we know why we should be citing references, but how exactly is it done? There are two things you need to do in order to cite a reference properly. The first is called an “in-line citation”. This just means you need to put something in-line with your main text body that tells the reader that you are citing a reference to support the claim you just made. For example: “The structure of DNA is that of a double helix (Watson & Crick, 1953).”

Here I’ve made a statement of fact and backed it up with the source material using an in-line citation, by putting the names of the authors in brackets, along with the year of publication. There are many different conventions on how to do in-line citations. Some use numerical references rather than names and dates. Which system you use will depend on which journal style guidelines you are following.

At the end of your article, in the references section, you expand on the in-line citations and provide the reader with a bibliography that lists every paper you cite along with all author names, dates of publication, article title, journal name, volume number, and page numbers. So the reference cited above would now look like:

References

Watson, J.D. and Crick, F.H. (1953). Molecular structure of nucleic acids; a structure for deoxyribose nucleic acid. Nature 171, 737-738.

The full reference provides all the information the reader needs to find the original source. In this style, the author names are in bold, followed by the year of publication and the paper title. Then comes the journal name in italics, the journal volume in bold and finally the page numbers.

This allows the reader to easily match each in-line citation with the full reference and then use the additional information the full reference provides in order to find the original article. Again, just like the in-line citation, the formatting of the full references in the bibliography will vary from journal to journal. It’s important that you follow the style guide of the journal very closely as they will refuse to publish your paper if you don’t.

Pffft. Style guide? But I’m just a student writing an assignment. Who cares? It’s not like I’m going to publish it anyway. Well, no, but consider this: you will be graded and in this instance you’ll pick up easy marks just for following simple instructions like “bold the author names” and “put the journal title in italics”. You don’t even have to think and you get marks for it. It’s like getting paid just for knowing how to tick a box.

Keeping track of in-line citations and updating the references (or bibliography) section at the end of a paper can be time consuming and annoying. To solve this problem, you should consider learning to use reference management software such as EndNote or Mendeley. These programs integrate into your word-processor and work a bit like iTunes for references. They store all your references in a library and allow you to easily add citations as you type, and automatically update the reference list at the end of the document as you go. They also make it easy to follow the appropriate referencing style guide by automatically formatting the references in whatever style you choose.

Improving Citation Style

So far, we’ve covered the basics of referencing, but you can improve your writing immensely by using more advanced citation techniques. The bibliography stays the same, but the way you use in-line citations can really improve the flow of your paper. So far, we’ve only covered the simplest way, that of sticking a single citation on the end of a sentence. There are other ways of citing papers, though, and mixing up how you approach this will improve the flow of your paper by avoiding boring repetition. There are two things to be mindful of here. Firstly, try to make sure that you aren’t ambiguous about what point is being backed up by what reference. Secondly, try not to rely on a single reference too much. Seeing the same paper cited over and over again tells the reader that you haven’t done a lot of reading on the topic, which suggests that you probably don’t really know what you’re talking about.

You can avoid placing a reference at the end of every sentence, even if you’re making claims in each one. If you spend two or three sentences establishing a single point, which is supported by a paper or two, then you can leave the citation until the end of the last sentence. This improves the flow of your paragraph and means the reader doesn’t have to see the citation in every line. However, it’s not a good idea to go on for too long without a citation, as the reader may become confused as to what part of the preceding text the citation is intended to support. This will have to be a judement call on your behalf, but I suggest a maximum of around three sentences.

Echidnas are small mammals that are covered in quills. Like other mammals, they are warm-bodied and secrete milk to feed their young. However, they differ from most mammals in that they do not give birth to live offspring, but lay eggs instead (Author, year).

This is a simplistic example of how you can avoid tedious repetition by grouping citations from a single source and leaving it until the end. If all the points made in each sentence are supported by the same paper(s), there's no reason to cite the same thing over and over. Be careful you don't let this get out of hand, or you'll confuse the reader into thinking you don't have any citations to support earlier claims. Doing this too often may also make it look like you haven't read widely on the subject. As a tool, it should only be used to help the reader by improving the flow of the paper, rather than to indulge the laziness of the author.

You can refer to papers directly. For example: “A report published by Fripp et al. (2014) suggests that [blah blah blah].” In this case, the in-line citation is actually the year in brackets. The author name is not required because you’ve already mentioned it. To find the original paper, the reader goes to the reference section and looks for a paper lead-authored by Fripp and published in 2014.

You can also cite within the flow of the sentence. This is often used if you’re contrasting papers with one another or listing discoveries; and is a very useful technique to help give the reader an overall picture of the state of the research into whatever it is you’re talking about. It not only helps to improve the flow of the sentence, but also leaves no ambiguity as to which paper supports which claim.

It has been shown that [thing a] (Wilson et al., 2008) and [thing b] (Gilmour and Cavanaugh, 2010) can negatively affect [system x]; although this is not always the case (Bowie, 2011; Hetfield et al., 2011).

In just a couple of lines, that sentence tells the reader a lot about what's going on in the field and who has done what to figure it out. Note also, the use of multiple citations within a single set of brackets at the end.

There are other ways of mixing up the flow of citations in a paper, and as you read and write more, it should start to come naturally to you. Hopefully, this section has given you some ideas about how to go about referencing. In particular, I hope you have a greater appreciation for the (often neglected) effort that goes into referencing and how it can impact the overall flow and structure of scientific writing.